Poetry

Lucille Clifton, 1936-2010

roots

call it our craziness even,

call it anything.

it is the life thing in us

that will not let us die.

even in death’s hand

we fold the fingers up

and call them greens and

grow on them,

we hum them and make music.

call it our wildness then,

we are lost from the field

of flowers, we become

a field of flowers.

call it our craziness

our wildness

call it our roots,

it is the light in us

it is the light of us

it is the light, call it

whatever you have to,

call it anything (Clifton, 1974)

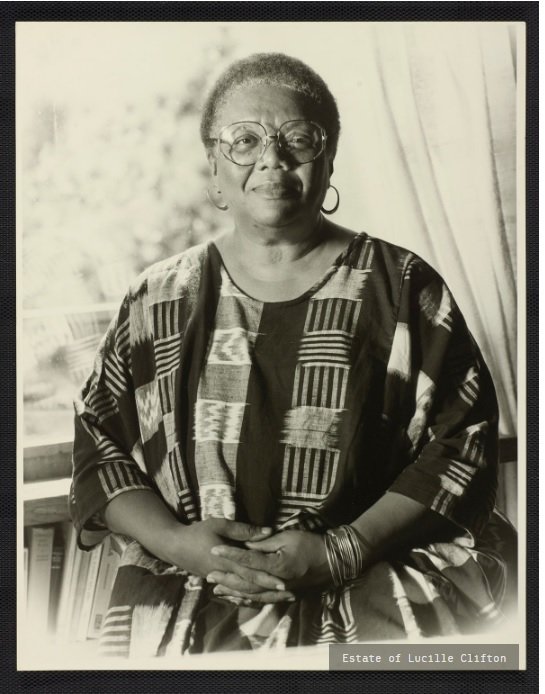

Portrait of Lucille Clifton

Source: The New York Times

In the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance, Lucille Clifton’s work surpasses the boundaries of time as she looks at her present being informed by years of memories and cultures of her ancestors. She writes about them in her memoir, Generations (1976). In an interview with Charles Rowell, Clifton mentions her motivations behind the memoir:

“I was thinking about the stories my father used to tell about his family. And I knew that his memory was an interesting story. It was interesting to me. Plus I felt very fortunate in knowing the name of the ancestor-of one of them-who came from Africa because we don't usually know that, you know, and because she came so late in the slave trade. 1830 was quite late, in fact” (Rowell, 1999, p. 56).

Clifton described herself “not as a Baltimore writer, but as a writer in Baltimore” (Yarborough, 2021). Orilonise Yarborough writes about the different spaces in Baltimore where Clifton shared her creative work. At a bar called Angel’s Tavern in Fells Point, she was a regular open mic poetry reader. As a trustee of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Clifton shared her experiences and engaged with young people encouraging them toward World Literature. Finally, her house was transformed into a cultural arts space for the Baltimore community. Yarborough observes that “As gentrification continues to threaten not only Black historic sites, but Black land ownership generally, the reclamation of this house not only brings the Cliftons back to their family homestead, but also opens space for new artists' voices to grow and thrive, just as Lucille Clifton’s did while living there” (Yarborough, 2021. para. 12).

“come celebrate with me that everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed”

Thus, wrote former poet laureate of Maryland from 1979-1985 Lucille Clifton in her poem won’t you celebrate me, commemorating her accomplishments as a black woman who became an established poet and author in the 20th century. Clifton was born in New York and went on to study at Howard University and then the State University of New York at Fredonia. She married Fred James Clifton, and they had six children. Clifton worked at various government departments including the New York State Division of Employment in Buffalo.

A breakthrough in her career as a writer was when she was recognized by Langston Hughes, one of the pioneers of Jazz Poetry and leaders of the Harlem Renaissance. Centered around the neighborhood of Harlem, New York, The Harlem Renaissance (1920-1930) can arguably be considered a consequence of The Great Migration which urged African Americans who had recently migrated up North to revive and restore their culture across the disciplines of literature, music, and scholarship. Hughes appreciated her work and published some of her poems in his anthology The Poetry of the Negro (1746-1949). Gaining accreditation as a poet, Clifton went on to publish her own poetry collection titled Good Times (1969). She later went on to teach literature and creative writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Columbia University, and Dartmouth College. Clifton had a deep connection with Baltimore, which showed up in her writing. She moved there with her family in 1967 and spent her last days in what is now known as The Clifton House in Windsor Hills, Baltimore.

Clifton produced numerous collections of poems like Two-Headed Woman (1980), Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems 1988–2000 (2000), and Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir 1969-1980 (1987). She was twice shortlisted for the infamous Pulitzer Prize and also received an Emmy Award.

Clifton’s works include a lot of themes like womanhood, aging, memory, and self-reflection. Her style of not capitalizing words is a unique feature of modern poetry written to oppose the strict old male literary tradition. Modifying the term “feminist,” author Alice Walker famously came up with the term “womanist” describing “a black feminist or feminist of color.” A common trope of womanist writing is going back to the roots of African culture, spiritism, and mysticism. Essentially, this means borrowing the ways of thinking, often through metaphors, of the ancestors who were forced to conform to a colonial way of living. Clifton’s work can be seen as dominant in the womanist elements. Scholar Rachel Elizabeth Harding observes this womanist tradition in her poems,

“I notice the persistence of Clifton’s relationship to the mystic, to mystery, to what she frequently calls ‘the light.’ On one hand, it appears in everyday places: the poet’s home; in her relationships with her children, especially her daughters; in her memories of her mother and the stories of women of her family; and in her husband’s dying... This impulse in Clifton’s poetry is strongly reminiscent of the way intimacy with spirit (that is, the very personal awareness of the ongoing accompaniment of spirit in the everyday lives of people) pervades the experience of devotees of Afro-Atlantic religions such as Brazilian Candomblé, Cuban Santeria, and Haitian Vodun. For Clifton, as for the adepts “called” to the service of the African deities, Spirit both attends and demands; and the physical experience of both is a shudder in the world” (Harding, 2014, p. 49-50)

Select Poems

testament (1987)

in the beginning

was the word.

the year of our lord,

amen. i

lucille clifton

hereby testify

that in that room

there was a light

and in that light

there was a voice

and in that voice

there was a sigh

and in that sigh

there was a world.

a world a sigh a voice a light and

i

alone

in a room.

the light that came to lucille clifton (1993)

came in a shift of knowing

when even her fondest sureties

faded away. it was the summer

she understood that she had not understood

and was not mistress even

of her own off eye, then

the man escaped throwing away his tie and

the children grew legs and started walking and

she could see the peril of an

unexamined life.

she closed her eyes, afraid to look for her

authenticity

but the light insists on itself in the world;

a voice from the nondead past started talking,

she closed her ears and it spelled out in her hand

"you might as well answer the door, my child,

the truth is furiously knocking.